Unit testing your code’s performance, part 1: Big-O scaling

When you implement an algorithm, you also implement tests to make sure the outputs are correct. This can help you:

- Ensure your code is correct.

- Catch problems if and when you change it in the future.

If you’re trying to make sure your software is fast, or at least doesn’t get slower, automated tests for performance would also be useful. But where should you start?

My suggestion: start by testing big-O scaling. It’s a critical aspect of your software’s speed, and it doesn’t require a complex benchmarking setup. In this article I’ll cover:

- A reminder of what big-O scaling means for algorithms.

- Why this is such a critical performance property.

- Identifying your algorithm’s scalability, including empirically with the

bigOlibrary. - Using the

bigOlibrary to test your Python code’s big-O scalability.

What’s this big-O thing again?

Big-O is a way to mathematically express the upper bound on an algorithm’s scalability. Understanding this requires covering three key aspects:

1. Algorithm (not implementation)

Let’s say you want to find if a value, the needle, is in a contiguous array of memory. The (almost trivially simple) algorithm to do so involves comparing each item in the array in turn to the needle, stopping when you’ve reached a value that matches. If you find the needle, you return true. If you never find the needle, you return false.

For a Python list, you could implement this yourself:

def contains(my_list, value):

for list_value in my_list:

if value == list_value:

return True

return False

or you could use Python’s built-in implementation:

result = value in my_list

The latter implementation is written in C, so it will be much faster, and so that’s what you’ll use in the real world. But the algorithm is the same in both cases.

2. Scalability (not speed)

We can’t really talk about the speed of an algorithm. Both the code examples above implement the same algorithm, but they have very different speeds.

But we can talk about scalability: how runtime changes as you increase the size of the inputs. For example, if you pass in a list of length 1,000, and then a list of size 10,000, we’d expect both implementations to take (approximately) 10× as much time to run since 10× as many comparisons would have to happen.

That means the runtime scales linearly with the size of the input. Big-O notation allows us to express this, by saying the algorithm is .

3. Upper bound (not an exact model)

This isn’t super-relevant to this article, but for completeness: big-O is an upper bound. Thus our algorithm is also , since .

Why knowing your algorithm’s scalability is so important

If you’re processing large amounts of data, algorithmic scalability is critical.

Consider two functions: function LinearA scales at , function QuadraticB scales at . It may be that for small inputs, QuadraticB is faster than LinearA; perhaps it’s heavily optimized. But given how they scale, there will be a size input such that QuadraticB is slower than LinearA. And once you hit that point, QuadraticB will get a lot slower as grows.

So it’s very useful to figure out what your algorithm’s scalability is! If it scales badly, it’s good to know that in advance, before you start using it in the real world. And maybe you can speed it up.

Determining your algorithm’s scalability

How can you tell what big-O your algorithm is?

- If you’re implementing an existing algorithm, someone else has likely documented this information.

- Or, you can read the code and think about it analytically. This is useful because it forces you to think about how your code works from a performance perspective.

- Finally, you can determine it empirically.

Let’s see how you can do the latter, using the bigO library, from the UMass lab that brought you the Scalene profiler.

It’s still pretty new, so I installed it from git to get the latest version:

pip install git+https://github.com/plasma-umass/bigO/

To empirically determine the big-O scaling of your code, you decorate your function with @bigO.track, which takes a function that takes the function’s inputs and returns the length of the data.

from bigO import track

def contains(my_list, value):

for list_value in my_list:

if value == list_value:

return True

return False

@track(lambda my_list, _value: len(my_list))

def tracked_contains(my_list, value):

return contains(my_list, value)

Then, you call the tracked function with data of varying sizes:

data = list(range(1_000_000))

for i in range(1, 50):

tracked_contains(data[100_000:i * 20_000], 999_999)

You then run the code, in this case stored in contains.py:

$ python contains.py

This writes out a bigO_data.json.

You can then convert this JSON file to a report:

$ python -m bigO --html

Infer performance for contains...

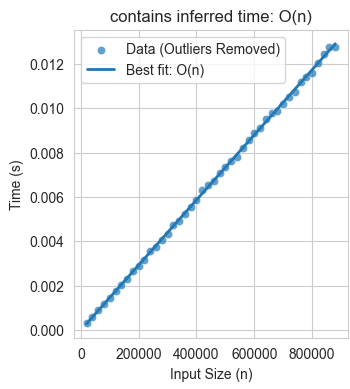

Inferred Bounds for contains

Best time model: O(n)

Best memory model: O(1)

bigO.html written.

Note: You’ll want to delete

bigO_data.jsonat this point, otherwise data from this run can get included in future runs, potentially resulting in garbage results.

Notice that the suggested time model is , pretty much what we’d expect. Here’s what the graph in the report look like:

Testing your code’s scalability with bigO

Now that you’ve determined the best big-O fit for your function, you can write a test that validates that. If it ever changes, the test will fail, helping you catch one particularly serious category of performance regressions. Here’s what a test looks like:

from contains import contains

from bigO import assert_bounds

def test_contains_scales_linearly():

# Create a series of inputs of different sizes:

data = list(range(1_000_000))

inputs = [

(data[100_000:i * 20_000], 123_456_789)

for i in range(1, 50)

]

# Function to calculate the length of inputs:

def input_length(data, _value):

return len(data)

# Assert the bound is O(n):

assert_bounds(

contains,

input_length,

inputs,

time="O(n)",

)

If we run this with pytest, the test passes as expected:

$ pytest test_contains.py

...

1 passed in 1.36s

Next, to demonstrate that the test works, I’ll modify contains() to make it scale badly:

def bad_contains(my_list, value):

my_list = my_list[:]

my_list.sort()

for list_value in my_list:

if value == list_value:

return True

return False

contains = bad_contains

Now, when I run the test:

$ pytest test_contains.py

...

FAILED test_contains.py::test_contains_scales_linearly -

bigO.bigO.BigOError: Time bound is supposed to be O(n)

but is actually O(n*log(n)).

1 failed in 1.51s

The test has caught a performance regression! In this case it was deliberately introduced, but of course it can also catch accidental regressions.

A good starting point, and next steps

The big-O testing I describe here is limited to catching one particular kind of performance regressions: a change in scalability. But for large amounts of data, this is the worst kind of regression, as it can take your program from being fast (or even slow) to being effectively unusable. So it’s an excellent first step.

The next step is to test for changes in algorithmic efficiency beyond just scalability, so you can tell if your code is getting slower (or faster). I’m hoping to cover that in another, future article.