Speeding up NumPy with parallelism

If your NumPy code is too slow, what next?

One option is taking advantage of the multiple cores on your CPU: using a thread pool to do work in parallel. Another option is to tune your code so it’s less wasteful. Or, since these are two different sources of speed, you can do both.

In this article I’ll cover:

- A simple example of making a NumPy algorithm parallel.

- A separate kind of optimization, making a more efficient implementation in Numba.

- How to get even more speed by using both at once.

- Aside: A hardware limit on parallelism.

- Aside: Why not Numba’s built-in parallelism?

From single-threaded to parallelism: an example

Let’s say you want to calculate the sum of the squared difference between two arrays. Here’s how you’d do it with single-threaded NumPy:

import numpy as np

def np_squared_diff(arr1, arr2):

return np.sum((arr1 - arr2) ** 2)

Because this function is summing values across the array, it can easily be parallelized by running the function on chunks of the array, and then summing those partial results. Here’s one way to do it, using only the Python standard library:

from concurrent.futures import ThreadPoolExecutor

# Start a thread pool with 8 threads, allowing using up to 8

# cores:

THREAD_POOL = ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=8)

def np_parallel_squared_diff(arr1, arr2):

num_chunks = len(arr1) // 100_000

# Split the arrays into chunks:

chunks1 = np.array_split(arr1, num_chunks)

chunks2 = np.array_split(arr2, num_chunks)

# For each chunk, run np_squared_diff() in a thread,

# then sum all the partial results:

return sum(

THREAD_POOL.map(np_squared_diff, chunks1, chunks2)

)

# Make sure both implementations give the same result:

A = np.arange(1, 10_000_000, dtype=np.int64)

B = np.arange(7, 10_000_006, dtype=np.int64)

assert np_squared_diff(A, B) == np_parallel_squared_diff(A, B)

How does their speed compare?

| Code | Elapsed microseconds ➘ | Peak allocated memory (bytes) ➘ |

|---|---|---|

np_squared_diff(A, B) |

30,893.9 | 160,009,094 |

np_parallel_squared_diff(A, B) |

7,350.9 | 12,342,931 |

(➘ Lower numbers are better)

Notice that not only does the parallel version return results faster, it also significantly reduces memory usage, since the temporary arrays that get created are much smaller. Reducing memory usage is useful in and of itself, but it also can help speed up code, as it can result in better utilization of the CPU’s memory caches.

A different source of speed

Thinking about the temporary arrays created by NumPy, you might realize that you don’t need temporary arrays at all: you can run this algorithm one value at a time, and sum those. Doing this in Python would be slow, but we can use the Numba library to compile Python code into machine code:

# Use 8 threads when parallelizing. We won't use this now,

# but it will become relevant later in the article.

import os

os.environ["NUMBA_NUM_THREADS"] = "8"

from numba import jit

# Decorating the function with numba.jit() compiles it to

# machine code the first time it's called. Releasing the GIL

# will be useful for parallelism, used later on.

@jit(nogil=True)

def numba_squared_diff(arr1, arr2):

result = 0

for i in range(len(arr1)):

result += (arr1[i] - arr2[i]) ** 2

return result

assert np_squared_diff(A, B) == numba_squared_diff(A, B)

Here’s a speed comparison of both single-threaded versions:

| Code | Elapsed microseconds ➘ | Peak allocated memory (bytes) ➘ |

|---|---|---|

np_squared_diff(A, B) |

31,397.3 | 160,009,094 |

numba_squared_diff(A, B) |

10,807.1 | 12,214 |

This is a distinct source of speed from parallelism. Or rather, distinct sources: the Numba version is likely faster both because it is doing less work (no need to read and write to temporary arrays) and doing work that is more aligned with how CPUs work (less pressure on memory caches, perhaps use of SIMD). Each of those is an independent source of speed, unrelated to parallelism.

Combining Numba with parallelism

Since the speed-up from Numba appears to be from distinct sources, we can get even more speed by adding in parallelism.

def numba_parallel_squared_diff(arr1, arr2):

num_chunks = len(arr1) // 100_000

chunks1 = np.array_split(arr1, num_chunks)

chunks2 = np.array_split(arr2, num_chunks)

return sum(

THREAD_POOL.map(numba_squared_diff, chunks1, chunks2)

)

assert np_squared_diff(A, B) == numba_parallel_squared_diff(A, B)

And here’s how all four versions compare:

| Code | Elapsed microseconds ➘ |

|---|---|

np_squared_diff(A, B) |

33,363.7 |

np_parallel_squared_diff(A, B) |

7,575.0 |

numba_squared_diff(A, B) |

10,911.8 |

numba_parallel_squared_diff(A, B) |

5,027.1 |

Aside: A hardware limit on parallelism

The parallel version of the Numba code is 2× as fast as the single-threaded version. While helpful, this is also a little strange: Numba was configured to use 8 threads, and my CPU has more than 8 cores. So one would expect rather more of a speedup, maybe not quite 8×, but certainly better than 2×.

The likely culprit is memory bandwidth: there’s only so much bandwidth

available for moving between RAM and the CPU. If the calculation is fast

enough, reading from memory becomes the bottleneck and prevents further

parallelism. Reducing memory usage can help in these situations. For

example, if the data could fit in an int32 instead of int64, twice

as many values could be read from RAM with the same amount of bandwidth.

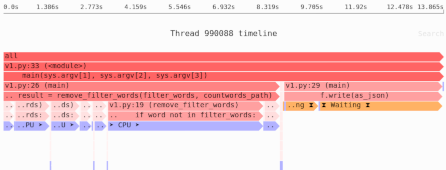

Aside: Numba’s built-in parallelism, and why I wouldn’t use it

In the example above I’m implementing parallelism outside of Numba. But Numba does have its own built-in way of using parallelism:

from numba import prange

@jit(parallel=True)

def numba_native_parallelism(arr1, arr2):

result = 0

# prange() will tell Numba to magically distribute the

# work in the `for` loop across multiple threads:

for i in prange(len(arr1)):

result += (arr1[i] - arr2[i]) ** 2

return result

assert np_squared_diff(A, B) == numba_native_parallelism(A, B)

Here’s how fast it is:

| Code | Elapsed microseconds ➘ |

|---|---|

numba_parallel_squared_diff(A, B) |

5,165.2 |

numba_native_parallelism(A, B) |

5,142.6 |

It’s just as fast as the custom parallel implementation, and requires less typing.

There, however, some downsides. If you’ve done any parallel programming,

you might feel very uncomfortable with result += <a value> running in

multiple threads. Since result is a shared global value, at first

glance having multiple threads write to it ought to result in race

conditions.

In practice, Numba detects this pattern and replaces it with summing partial results. Unfortunately, this detection doesn’t always work, and when it fails, it fails silently with no compiler warning. For example:

@jit(parallel=True)

def numba_native_parallelism_bad(arr1, arr2):

result = np.zeros((1,), dtype=np.int64)

for i in prange(len(arr1)):

result[0] += (arr1[i] - arr2[i]) ** 2

return result[0]

print("Correct result:", np_squared_diff(A, B))

print()

for _ in range(5):

print("Bad parallel result:", numba_native_parallelism_bad(A, B))

Correct result: 359999964

Bad parallel result: 18000000

Bad parallel result: 36000000

Bad parallel result: 36000000

Bad parallel result: 18000000

Bad parallel result: 18000000

Parallelism is useless if you get wrong results. After all, If you’re OK with getting wrong results and the only thing you care about is speed, you can write a function like this:

def superfast(arr1, arr2):

return 0

Given how easy it is to write silently buggy code with Numba’s built-in parallelism, I would not personally use it. If you need to write more complex parallel code, use Rust, which was created specifically to solve the problem of code that is safe, fast, and parallel at the same time.

Parallelism and more

Parallelism can make your code faster, and so you should use it if possible. But there are additional ways to speed up your code, and they can combine with parallelism to make your code even faster. If you need your code to be fast, you should use all of them!