Beyond multi-core parallelism: faster Mandelbrot with SIMD

What do you do when computation is too expensive?

Recently I’ve had a brilliant business idea: Mandelbrot-as-a-Service! Instead of companies calculating their own fractals, I will do it for them, freshly calculated in the cloud, with no work on their part. And by using cloud computing, I will be able to scale to the no-doubt vast number of customers who will be paying for my ingenious new service.

I have two goals:

- Speeding up results: The faster I can return fractals, the happier my customers will be.

- Reducing costs: If I can pay my cloud provider less for computing, my profits will go up!

Unfortunately, since I will only be selling freshly calculated and warm-from-the-CPU Mandelbrots, I can’t rely on caching.

What would you do in this situation?

One obvious approach is parallelism: threading or multiprocessing. This will speed up results, so it’s definitely worth doing, but it won’t reduce my costs. If we use 10 cores instead of 1 core, the service will return results ten times faster, but we’ll have to pay approximately 10× as much, since we’ll be using 10× larger instances.

However, if we can figure out how to speed up calculations on a single core, this will contribute to both our goals. We’ll both get faster results, compounded by any multi-core processing, and reduce compute costs.

In this article we will:

- Quickly go over a standard Mandelbrot implementation, written in Rust.

- Discuss why it can be tricky to optimize the Mandelbrot algorithm on a single CPU core.

- Demonstrate how you can in fact do so, by using masked SIMD operations.

- Trivially add on multi-core parallelism, using Rust’s Rayon library.

- PROFIT!

Mandelbrot in Rust

The Mandelbrot calculation is written in Rust for two reasons:

- It’s an excellent language for writing Python extensions.

- I found a pre-written version that includes both a scalar (normal) implementation and a SIMD implementation.

The code examples and images in this page are copyright the Rust developers and licensed under the MIT or Apache 2.0 licenses, your choice. I’ve ported the original code to newer Rust SIMD APIs, and simplified them for readability. I’ll link to the full project at the end of the article.

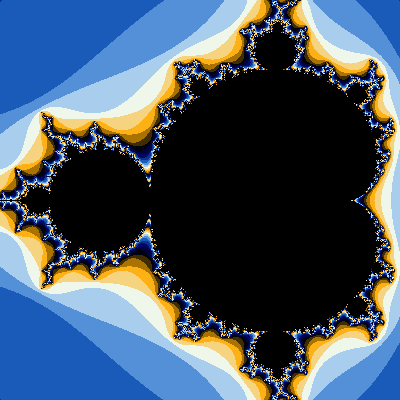

We want to get pretty images like this:

The calculation involved is fairly simple. For each pixel we have a starting complex number, and we repeatedly transform it until it “diverges” from a constant threshold (4.0 by default). The number of transformations gets converted into the color for the corresponding pixel:

/// Complex number

#[repr(align(16))]

#[derive(Copy, Clone)]

struct Complex {

real: f64,

imag: f64,

}

/// Returns the number of iterations it takes for the

/// Mandelbrot sequence to diverge at this point, or

/// `ITER_LIMIT` if it doesn't diverge.

fn get_count(start: Complex) -> u32 {

let mut current = start.clone();

for iteration in 0..ITER_LIMIT {

let rr = current.real * current.real;

let ii = current.imag * current.imag;

if rr + ii > THRESHOLD {

return iteration;

}

let ri = current.real * current.imag;

current.real = start.real + (rr - ii);

current.imag = start.imag + (ri + ri);

}

// Rust has an implicit return for expressions

// without a semi-colon at the end of a function:

ITER_LIMIT

}

Other code, not shown, creates a complex number for each pixel, calls get_count() on it, and transforms the result into a color for that pixel.

Some problems optimizing this code

As I cover in my upcoming book on optimizing computational code, there are different ways we can try to optimize code. Some approaches we won’t be pursuing here:

- Removing unnecessary work: This is going to be difficult in this case—there’s not a lot of wasted effort here within the calculation. A real Mandelbrot service could use caching so it doesn’t have to recalculate common outputs.

- Relaxing the precision of results: We could, perhaps, tweak our calculation to be a little less accurate as a trade-off for faster results, but for now we want the highest quality Mandelbrot money can buy.

What we’re left with is trying to take advantage of modern CPU features that enable parallelism within a single core. Importantly, this doesn’t involve threads or processes, this is having a single thread run faster because somehow the CPU will do multiple things at once.

One mechanism is transparently applied by the CPU: instruction-level parallelism.

Unfortunately, the way the algorithm works makes this sort of parallelism difficult.

In each iteration the current calculation relies on the previously calculated current value, so at best we can get parallelism within a single loop iteration, not across iterations.

Can we use SIMD to optimize Mandelbrot?

The approach we will use to optimize Mandelbrot is SIMD: Single Instruction Multiple Data. These are specialized CPU instructions that allow you to, for example, add 4 values at once with a single instruction, instead of the usual one value at a time.

For example, if we’re operating on 4 values at once, we can pack two vectors of 4 int64 into two special SIMD “registers” (special CPU memory slots for variables used in computation), and add all of them with a single special instruction:

[1, 3, 5, 1]

SIMD add

[2, 4, 2, 8]

=

[3, 7, 7, 9]

Now, if you look at our Mandelbrot algorithm, it’s still not clear how operating in batches can help.

We can process 4 or 8 pixels at once… but the number of iterations in the for loop will be different for different starting values.

So it seems like we can’t just keep doing the same operations to all the pixels.

This is where SIMD “masking” comes in: it’s possible to operate differently on different indexes (called “lanes” in SIMD terminology), by using a mask. So we can create a mask that indicates which lanes we’re done processing (because they’ve diverged and hit the threshold) and which lanes we need to keep processing. That means we can do slightly different operations on different values while still processing 8 values per CPU instruction.

A SIMD implementation of Mandelbrot in Rust

Portable SIMD in Rust still isn’t stable, so you have to do a bit more work to use it.

First, we need to use a nightly (unstable) compiler; I dropped a rust-toolchain.toml file in the repository:

[toolchain]

channel = "nightly-2024-08-26"

Next, in src/lib.rs we can enable the experimental portable SIMD feature by adding this to the top of the file:

#![feature(portable_simd)]

We can now write a SIMD implementation of the same algorithm we saw above:

use std::simd::prelude::*;

// Instead of storing a single value, we store a vector of 8

// values; each index in the vector, from 0 to 7, is a

// different "lane". Because they're special SIMD types,

// they'll get processed as a batch if the CPU supports it,

// using special SIMD "registers" (CPU memory slots), which

// can be 128-bit, 256-bit, or 512-bit.

type u64s = u64x8;

type u32s = u32x8;

type f64s = f64x8;

/// Storage for complex numbers in SIMD format. The real and

/// imaginary parts are kept in separate registers.

#[derive(Clone)]

struct Complex {

real: f64s,

imag: f64s,

}

/// Returns the number of iterations it takes for the

/// Mandelbrot sequence to diverge at this point, or

/// `ITER_LIMIT` if it doesn't diverge. We process 8

/// values at a time!

fn get_count(start: &Complex) -> u32s {

// Instead of getting a single value as input, we

// get a batch of 8.

let mut current = start.clone();

// Instead of having a single return value, we

// are going to return a vector of 8 values. We

// initialize all of them to 0.

let mut count = u64s::splat(0);

// This is the threshold we will compare our current

// 8 values to, turned into an SIMD vector of 8 values.

let threshold_mask = f64s::splat(THRESHOLD);

for _ in 0..ITER_LIMIT {

// This looks just like the scalar operations, but

// we're multiplying 8 values against 8 values.

// Hopefully our CPU has the instructions that

// allows us to do all of these at once.

let rr = current.real * current.real;

let ii = current.imag * current.imag;

// Keep track of those lanes which haven't diverged

// yet. The other ones will be masked off.

//

// For example:

//

// [2.3, 4.2, 4.0, 4.1, 0.5, 0.7, 2.3, 5.0]

// simd_le

// [4.0, 4.0, 4.0, 4.0, 4.0, 4.0, 4.0, 4.0]

// ↓

// [ 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0]

let undiverged_mask = (rr + ii).simd_le(

threshold_mask);

// Stop the iteration if they all diverged.

if !undiverged_mask.any() {

break;

}

// For undiverged lanes add 1, for diverged lanes

// add 0. This is the trick that allows us to process

// different lanes differently!

count += undiverged_mask.select(

u64s::splat(1),

u64s::splat(0)

);

// Same calculation as scalar algorithm, but

// hopefully doing 8 operations in a single SIMD CPU

// instruction.

let ri = current.real * current.imag;

current.real = start.real + (rr - ii);

current.imag = start.imag + (ri + ri);

}

count.cast()

}

Again, other code not shown here creates Complex instances, each with 8 values in them, and then turns the results of get_count() into color values for the corresponding pixels.

Next, we want to compile this code. This is a portable SIMD library, so it can use different SIMD instructions. And that’s important because different CPU models have different SIMD instructions. For example, AVX-512 SIMD instructions are available on some x86-64 CPUs, but not all (my computer lacks them!).

So when we compile our code, as a first pass we tell the compiler to target the current CPU. This means the binary won’t be portable; something compiled on my machine might not work on a 10-year-old computer. But it does enable Rust to use the best SIMD instructions available locally.

$ RUSTFLAGS="-C target-cpu=native" cargo build --release

This lack of portability is a problem, but it’s also solvable. I hope to write a follow-up article explaining how to make portable binaries that can still take advantage of whatever CPU features are available.

Comparing performance: scalar vs. SIMD

So we’ve rewritten our algorithm to use SIMD—is it actually faster? To find out, I generated 3200×3200 images and measured the run time of the two versions:

| Version | Runtime (single core) |

|---|---|

| Scalar | 617 ms |

| SIMD | 135 ms |

The SIMD version is indeed much faster.

Utilizing multi-core parallelism with Rayon

So far we’ve been running on a single core. But we do want to get results to users as fast as possible, so we want to take advantage of multiple cores. And of course there’s the question of whether the speed improvement we’ve seen will be sustained once multiple cores are used.

Since we’re using Rust, parallelism is easy with the Rayon crate. We add it as a dependency:

$ cargo add rayon

Now, we just need to make sure the APIs are available:

use rayon::prelude::*;

We find the core iterator that drives our logic, e.g. this loop in the SIMD implementation:

out.chunks_mut(width_in_blocks)

.enumerate()

// ...

And we change the chunks_mut() to par_chunks_mut(), to iterate in parallel, automatically using all our CPU cores:

out.par_chunks_mut(width_in_blocks)

.enumerate()

// ...

And—that’s it! We now have multi-core parallelism using a thread pool managed by Rayon.

Here’s the performance I get on my i7-12700K CPU (with hyperthreading and turboboost disabled):

| Version | Runtime (single core) | Runtime (multi-core) |

|---|---|---|

| Scalar | 617 ms | 45 ms |

| SIMD | 135 ms | 17 ms |

The speedup we get from SIMD isn’t quite as high in the multi-core case, but it still gives us a significant boost to performance.

Want to see the full, runnable project? It’s up on GitHub.

The big picture: you can go faster on a single core

Our initial implementation was written in a fast, compiled language—but by switching to SIMD, we managed to make it faster while still running in a single thread on a single CPU core. Using SIMD cut our costs by somewhere between 78% and 62%, and it benefits us even when we switch to multi-core parallelism.

And we did this with fairly generic SIMD code, with a fairly simple translation from scalar to SIMD code. It’s quite possible one could do better.

Using SIMD is, of course, just an example. In other situations other optimization techniques will give you the same benefits: faster results and lower costs. Multi-core parallelism is immensely useful, but it shouldn’t be the only trick in your performance bag.