When your data doesn’t fit in memory: the basic techniques

You’re writing software that processes data, and it works fine when you test it on a small sample file. But when you load the real data, your program crashes.

The problem is that you don’t have enough memory—if you have 16GB of RAM, you can’t load a 100GB file. At some point the operating system will run out of memory, fail to allocate, and there goes your program.

So what can you do? You could spin up a Big Data cluster—all you’ll need to do is:

- Get a cluster of computers.

- Spend a week on setup.

- In many cases, learn a completely new API and rewrite all your code.

This is a bit of exaggeration, to be fair, since you can spin up Big Data clusters in the cloud, but it can still be expensive and frustrating; luckily, in many cases it’s also unnecessary.

You need a solution that’s simple and easy: processing your data on a single computer, with minimal setup, and as much as possible using the same libraries you’re already using. And much of the time you can actually do that, using a set of techniques that are sometimes called “out-of-core computation”.

In this article I’ll cover:

- Why you need RAM at all.

- The easiest way to process data that doesn’t fit in memory: spending some money.

- The three basic software techniques for handling too much data: compression, chunking, and indexing.

Followup articles will then show you how to apply these techniques to particular libraries like NumPy and Pandas.

Why do you need RAM at all?

Before we move on to talking about solutions, let’s clarify why the problem exists at all. Your computer’s memory (RAM) lets you read and write data, but so does your hard drive—so why does your computer need RAM at all? Disk is cheaper than RAM, so it can usually fit all your data, so why can’t your code just limit itself to reading and writing from disk?

In theory, that can work. However, even the more modern and fast solid-state hard drives (SSDs) are much, much slower than RAM:

- Reading from SSDs: ~16,000 nanoseconds

- Reading from RAM: ~100 nanoseconds

If you want fast computation, data has to fit in RAM, otherwise your code may run as much as 150× times more slowly.

The 💰 solution: more RAM

The easiest solution to not having enough RAM is to throw money at the problem. You can either buy a computer or rent a virtual machine (VM) in the cloud with lots more memory than most laptops. In November 2019, with minimal searching and very little price comparison, I found that you can:

- Buy a Thinkpad M720 Tower, with 6 cores and 64GB RAM, for $1074.

- Rent a VM in the cloud, with 64 cores and 432GB RAM, for $3.62/hour.

These are just numbers I found with minimal work, and with a little more research you can probably do even better.

If spending some money on hardware will make your data fit into RAM, that is often the cheapest solution: your time is pretty expensive, after all. Sometimes, however, it’s insufficient.

For example, if you’re running many data processing jobs, over a period of time, cloud computing may be the natural solution, but also an expensive one. At one job the compute cost for the software I was working on would have used up all our projected revenue for the product, including the all-important revenue needed to pay my salary.

If buying/renting more RAM isn’t sufficient or possible, the next step is to figure out how to reduce memory usage by changing your software.

Technique #1: Compression

Compression means using a different representation for your data, in a way that uses less memory. There are two forms of compression:

- Lossless: The data you’re storing has the exact same information as the original data.

- Lossy: The data you’re storing loses some of the details in the original data, but in a way that ideally doesn’t impact the results of your calculation very much.

Just to be clear, I’m not talking about a ZIP or gzip file, since those typically involve compression on disk. To process the data from a ZIP file you will typically uncompress it as part of loading the files into memory. So that’s not going to help.

What you need is compression of representation in memory.

For example, let’s say your data has two values, and will only ever have those two values: "AVAILABLE" and "UNAVAILABLE".

Instead of storing them as a string with ~10 bytes or more per entry, you could store them as a boolean, True or False, which you could store in 1 byte.

You might even get the representation down to the single bit necessary to represent a boolean, reducing memory usage by another factor of 8.

You can read more about lossless compression in Pandas, lossy compression in Pandas, and lossless compression in NumPy.

Technique #2: Chunking, loading all the data one chunk at a time

Chunking is useful when you need to process all the data, but don’t need to load all the data into memory at once. Instead you can load it into memory in chunks, processing the data one chunk at time (or as we’ll discuss in a future article, multiple chunks in parallel).

Let’s say, for example, that you want to find the largest word in a book. You could load all the data into memory at once:

largest_word = ""

for word in book.get_text().split():

if len(word) > len(largest_word):

largest_word = word

But since in our case the book doesn’t fit into memory, you could instead load the book page by page:

largest_word = ""

for page in book.iterpages():

for word in page.get_text().split():

if len(word) > len(largest_word):

largest_word = word

You are using much less memory, since you only have one page of the book in memory at any given time. And you still get the same answer in the end.

You can learn more about chunking in Pandas, and NumPy storage formats that make chunking possible.

Technique #3: Indexing, when you need a subset of the data

Indexing is useful when you only need to use a subset of the data, and you expect to be loading different subsets of the data at different times.

You could solve this use case with chunking: load all the data every time, and just filter out the data you don’t care about. But that’s slow, since you need to load lots of irrelevant data.

If you only need part of the data, instead of chunking you are better off using an index, a summary of the data that tells you where to find the data you care about.

Imagine you want to only read the parts of the book that talk about aardvarks. If you used chunking, you would read the whole book, page by page, looking for aardvarks—but that would take quite a while.

Or, you can go to the end of the book, where the book’s index is, and find the entry for “Aardvarks”. It might tell you to read pages 7, 19, and 120-123. So now you can read those pages, and those pages only, which is much faster.

This works because the index is much smaller than the full book, so loading the index into memory to lookup the relevant data is much easier.

The simplest indexing technique

The simplest and most common way to implement indexing is by naming files in a directory:

mydata/

2019-Jan.csv

2019-Feb.csv

2019-Mar.csv

2019-Apr.csv

...

If you want the data for March 2019, you just load 2019-Mar.csv—no need to load data for February, July, or any other month.

You can learn more about indexing in Pandas, as well as some optimizations when loading indexed data from a SQL database.

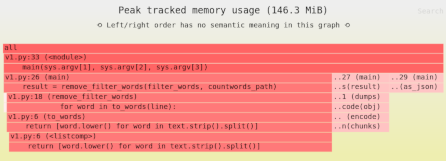

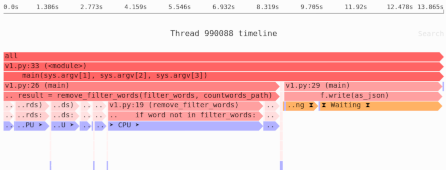

Note: Whether or not any particular tool or technique will help depends on where the actual memory bottlenecks are in your software.

Need to identify the memory and performance bottlenecks in your own Python data processing code? Try the Sciagraph profiler, with support for profiling both in development and production macOS and Linux, and with built-in Jupyter support.

Next steps: applying these techniques

The easiest solution to lack of RAM is spending money to get more RAM. But if that isn’t possible or sufficient in your case, you will one way or another finding yourself using compression, chunking, or indexing.

These same techniques appear in many different software packages and tools. Even Big Data systems are built on these techniques: using multiple computers to process chunks of the data, for example.

In follow-up articles I will show you to how to apply these techniques with specific libraries and tools: NumPy, Pandas, and even ZIP files. If you want to read these articles as they come out, sign up for my newsletter in the form below.